Historical background

At a casual

glance the city of Cardiff appears to be very much a Victorian construction-its

city streets exhibiting a mixture of Gothic and Classical Revival architecture

reflecting the confidence, surety and economic success of its Victorian heyday

as the largest coal port in the world. This ascent begun in earnest with the

construction of the Bute Dock in 1839 and culminated with the signing of the

first million-pound business deal at the Coal Exchange in 1904.

Cardiff’s

ancient past though is not so easy to spot. Even Cardiff’s medieval castle

appears, at least on the surface, to be a Victorian creation of pure Gothic

fantasy, the result of a joint enterprise between the fabulously wealthy Third

Marquess of Bute John Crichton-Stuart (1847-1900) with his devout vision, and the

genius of architect William Burges (1827-1881). Despite its Victorian appearance,

the city of Cardiff has a history that stretches back to the Roman period.

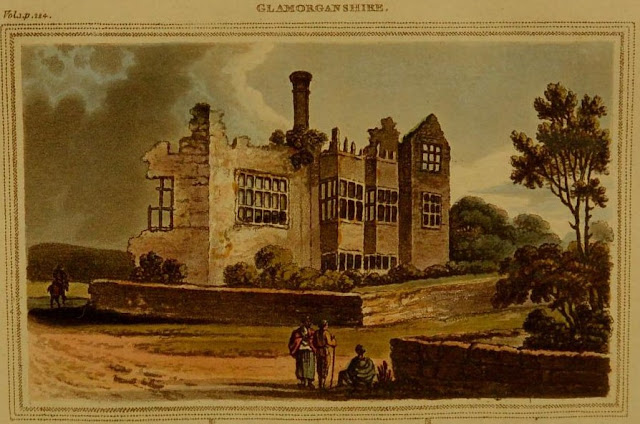

(Mid eighteenth-century colour print of the north-west view Cardiff by English engravers and printmakers Samuel and Nathaniel Buck)

The founding of the modern town of Cardiff coincided with the Norman invasion of South Wales during the late eleventh century. Cardiff Castle, itself built upon the site of a ruined Roman fort, was likely constructed-or at least expanded, under the auspice of Norman Baron Robert Fitzhamon (d 1107) and became the centre for the newly established medieval lordship of Glamorgan. Much like the Roman fort at Cardiff and its associated vicus town, a settlement also developed around the medieval castle which would provide the founding of the city of Cardiff, the medieval street layout of which is still by and large retained today.

Cardiff during

the medieval period thrived as a borough and as a port. Cardiff, along with

Llantwit Major, had one of the largest populations of medieval Wales numbering

over 2000 people and despite a number of attacks, rebellions and incursions by

aggrieved Welsh lords, including the audacious kidnapping and ransom of Robert, earl of Gloucester by the brave but dangerous lord of Senghenydd, Ivor Bach in

1158, as told to us by Geoffrey of Wales, Cardiff thrived as a town.

Simmering Welsh

resentment to Anglo-Norman rule however finally boiled over on a national scale

during the Glyndwr Rebellion (1400-1415) and Cardiff Castle and town were almost

completely destroyed in around 1404. It took Cardiff over one hundred years to

recover from this event. Once the medieval lordship of Glamorgan was dissolved in

1536 under the Act of Union between England and Wales, Cardiff became the county

town of the newly established shire of Glamorgan.

Post Medieval Cardiff

Cardiff during

the post medieval period once again began to thrive. Despite Cardiff’s partly

ruined medieval castle providing the main point of interest for visitors, as indeed

it still does today, it did not go unnoticed by tourists that Cardiff was

beginning its ascent out of obscurity.

The port of Cardiff during the latter part of the eighteenth century was a busy one with trade from Bristol and other places increasing as well as facilitating the prospering export markets of iron and coal. The innovations of the industrial revolution, such as the Monmouthshire Canal system which was constructed in the latter part of the eighteenth century, slowly began to impose themselves upon this small town-a precursor to the innovation of the steam railway, which ultimately enabled the port of Cardiff to export coal on a scale never before seen to all parts of the world.

Cardiff Town’s

population in 1801 however, had hardly changed from the medieval period with a

total population of 1870 inhabitants at this time. This is in stark contrast to

the latter part of the same century as in 1871 Cardiff’s population had

bourgeoned to 56,911 people (including Llandaff).

It is very much

the lives of Cardiff town’s ordinary people and the views and impressions of

Cardiff’s visitors during the Georgian period that is the focus of this article

which we hope will serve to give an insight into ordinary life. The paintings

and photographs will also serve to highlight the magnitude of change to Cardiff

which occurred during the Victorian period, as architecturally during the

Georgian period Cardiff still had very much the appearance of a typical early post-medieval

town being comprised of a great number of wooden Tudor-Stuart period buildings

and elegant Georgian townhouses. All this was to change upon the advent of

Cardiff Dock’s assent to the world stage during the Victorian period, when most

of Cardiff’s ancient architecture began to be swept-away when the city that we

know today was born and the surrounding landscape quickly developed.

Impressions of Cardiff Town

The perception

that Cardiff had upon visitors during the Georgian period appears to have overall

been a positive one. Despite being a small town, nearly all of Cardiff’s

Georgian visitors were impressed by Cardiff’s neat-clean streets and layout.

William

Gilpin writing in 1770 commented that:

‘Cardiff lies

low, though it is not unpleafantly feated on the land fide among woody hills.

As we approached it appeared with more of the furniture of antiquity about it

than any town we had feen in Wales ; but on the fpot the pidurefque eye finds

it. too entire to be in full perfection.’

Edward Daniel

Clarke writing in 1791 observed that:

‘Cardiff, having the benefit of a good harbour, carries on a brisk trade with Bristol, and other places, and has of late considerably increased its commercial importance: but perhaps its chief interest with tourists will be derived from its castle.’

(Mid nineteenth century painting showing the Cardiff that our Georgian visitors would've been familiar with. Source, Museum of Wales)

The Rev J Evans upon visiting Cardiff in 1803

was clearly impressed by what he saw, writing:

‘This is, for

Wales, a handsome town, consisting of several spacious streets of decent

houses, well pitched and paved. The inns, are good, and the inhabitants civil.’

J.T Barber

writing in 1803 was of a similar opinion to the Rev J Evans in that:

‘On entering

Cardiff, the capitol of Glamorganshire, between the ivy-mantled walls of its castle

and the mouldering ruin of a house of White Friars, we were much pleased with

the aspect of the town, nor were we less so on a closer examination of its neat

and well-paved streets ; it appearing to us one of the cleanest and most agreeable

towns in Wales’.

Zoologist and

writer Edward Donovan who visited in 1804 was also impressed by what he saw and

narrated:

‘The town of

Cardiff, considered as a sea port, lias a remarkably neat appearance. One of

the principal streets extends in a southerly direction nearly from the castle

to the new quay. Adjoining the latter, a commodious range of buildings has been

very recently erected, which may be justly deemed an ornament to the place :

the houses appear to be chiefly, if not exclusively, in the occupation of the

merchants, proprietors, and agent's engaged in the commerce of the port, and

especially of those connected with the mining speculations of the inland parts

of the country.’

Edward further

stated that:

‘The influx

of strangers to Cardiff during the summer months, is astonishingly great as may

be conceived from the large proportion of lodging houses in the town: nor can

the travelling business of the place be inconsiderable, since that alone

supports two large inns upon an extensive scale, besides several smaller houses

of public accommodation,’

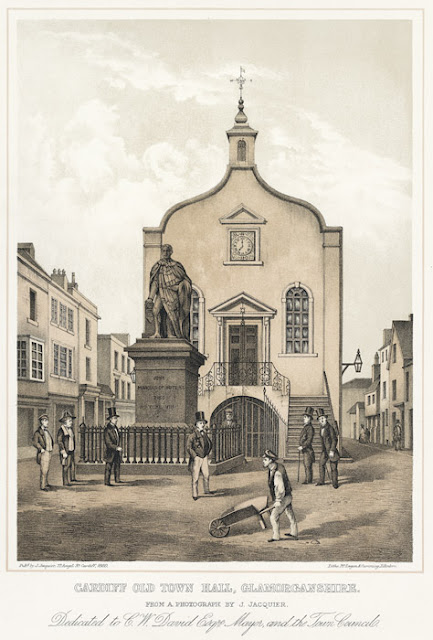

(Mid nineteenth century view of Cardiff's old town hall which once stood in the middle of St Mary Street)

Outrage at the Angel Inn

Despite the

favourable impression Cardiff made upon Edward Donovan, he was more than a

little indignant at being forced to pay a guinea (a gold coin worth twenty-one

shillings) for a single night’s lodgings at the Angel Inn.

‘No people in the Principality know better how to profit by the liberality, or rather the credulity of strangers than the Cardiff inn-keepers; they have little of that courtesy by which this description of people are so uniformly distinguished in other Welsh towns; and when the place is pretty full of company, which often happens in the Summer, we have commonly found that their extortion could be only paralleled by their incivility. — “I suppose you are a stranger to Cardiff,” said one of the servants of the Angel inn, with a supercilious air not easily described, when I once complained that a guinea was certainly too much for a very indifferent bed, with which my hostess had accommodated me in an adjacent house for the preceding night. — “ Surely, (I made answer ) although such a sum may be given during the time of the races, or the assizes, that cannot be a customary charge.” — “Not a constant charge, I grant,” replied the girl, “ but a common one when the town is very full of company, I assure you.’

Industry

The fact that the

antiquated town of Cardiff was becoming entwined within the Industrial

Revolution and was beginning its journey towards becoming a port of global

significance was not lost upon visitors.

The Rev J Evans observed:

‘The iron

works of the adjacent country have greatly added to the consequence of this

place. By an Act which passed in 1790, a canal was cut from Penarth Point to

the Cyfartba iron works, near Merthyr Tydvil ; an extent of twenty-five miles,

which has greatly facilitated the means of, conveying so ponderous an article

of commerce to a market.’

(Late nineteenth century view of the canal that once ran adjacent to Cardiff Castle. Source, Wales Online)

Edward

Donovan noted that:

‘What tends

materially to promote the trade of Cardiff; is the facility with which a

constant intercourse is maintained between the inhabitants, and those of the

interior part of Glamorganshire, the great centre of the celebrated iron works

of this county. The canal communicating with Merthyr Tydvil and Aberdare, both

which lie at the distance of about five and twenty from Cardiff port.

The expenses attending the construction of this canal has already exceeded fifty thousand pounds ; the greater part of which has been defrayed by the iron masters of Merthyr and its vicinity, whose immediate interest this noble undertaking is so peculiarly calculated to advance, by affording a speedy conveyance for the produce of their mines and forges, at an easy charge, to a convenient depot for shipping it to the respective markets and twenty miles from the Cardiff port, is an improvement of modern day’s.’

Cardiff Castle

Cardiff Castle

in the latter part of the Georgian period began to attract the interest of both

casual visitors and antiquarians. All it seems gravitated towards this ancient structure

and eagerly sought a tour of Cardiff’s medieval castle.

It appears however, that our Georgian visitors were not very impressed by the unsympathetic reconstruction works which were undertaken by successive owners throughout the latter part of the eighteenth century. A large part of these works included the demolition of the outer bailey of the Norman keep, the cross-wall, the medieval shire-house and Knight’s Hall on the advice of celebrated landscape architect Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. The ‘capability’ moniker was derived from Lancelot’s proclivity of telling clients that their properties had ‘capability for improvements’. Our erstwhile Georgian visitors to Cardiff Castle evidently thought otherwise.

Restoration

works

The Rev J Evans commented that:

‘The

modernization of the present mansion, and the close mown grass and gravel walks

of the area, but ill accord with the stately architecture and ivied walls of

this proud pile, which has withstood the storms of seven centuries.’

Edward Donovan narrated that:

‘Cardiff Castle

is a noble structure, occupying a great extent of ground on the north side of

the town. About seven years ago the habitable part of the castle, a fine suite

of apartments in an ancient style of grandeur that forms the western wing of

the building, was to have received a very complete repair, when the death of the possessor put a period, for a while, to

the progress of those improvements. — Before this time, the castle had

undergone amendments that were far less gratifying to the peculiar taste of the

antiquary, than to the admirers of modern reformation. Grose laments the

depredations which it had sustained before his days, but it suffered again

materially within the last twenty or thirty years, the space of time elapsed

since he saw it. The courts and walls that formerly extended across the area,

have vanished, and the venerable keep divested of these appurtenances, now

trimly crests the summit of a verdant eminence on one side of a smoothly mown

grass plat.’

Donovan even notes that there were plans at the time to convert the keep into a dancing room.

Daniel Clarke writing in 1791 lamented that:

‘Cardiff

Castle, a seat of the Marquis of Bute, (Baron Cardiff and Earl of Windsor), was

until lately a Gothic structure of considerable elegance; but having undergone

a repair, without attention to the antique style of architecture, it presents a

motley combination, in which the remaining Gothic but serves to excite our

regret for the greater portion destroyed.’

It was this extensive re-modelling which caused the death of Thomas Llewellin when working at Cardiff Castle in 1777. Thomas died when a wall fell on him, crushing him to death. Thomas was almost certainly involved with the destructive renovation of the castle conducted under the auspices of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown on behalf of the first Marquees of Bute in the 1770s.

Secret

tunnels

Edward Daniel Clarke narrates an anecdote

regarding a secret tunnel that was said to exist within the castle:

‘A fubterreanean

paffage [subterranean passage] , the old bugbear of all caftles, is faid to

continue from this place to a priory at fome diftance and what added a little

to the veracity of the ftory [story] the pefon [person] who conducted us over the ruins affured me

that he had ventured to explore it himfelf, as far as he could proceed, but

that finding his candle go out, Aid the damps become exceffive, he returned| and

fince that time, the entrance has been buried with rubbish’

Crime and Punishment in Georgian Cardiff

The Georgian town of Cardiff is also of interest for the behaviour of its inhabitants. Their mishaps, adventures and sometimes deviant behaviour are of great interest to those who are curious about past-times.

Theft was common in eighteenth century Cardiff. In 1740 a labourer by the name of Thomas Harris stole what was described as a ‘gold quarter Guinea’ (5 shillings and 3pence). Thomas had made the mistake of confiding in a relation, Edward Harris. Edward, who was a barber, was clearly of a more honest disposition than his brother and did the right thing ensuring that Thomas returned the coin to its rightful owner.

In 1732 Cardiff man, William Harry (sailor) was convicted of stealing a purse which contained £17. 2s in coins. The purse was taken from a boat which belonged to a man called Robert Priest. William’s fate is not recorded but being shipped to the American colonies to work on the plantations for a number of years was common. This is exactly what happened to Thomas Harry in 1735 when he was convicted at Cardiff of burglary, he was initially sentenced to death. It would appear that the records tell us that the court was disposed to be lenient and this was commuted to seven years slave labour on a plantation in the American colonies. It is not noted if Thomas ever returned.

Violence was

common in Georgian Cardiff, but a number of incidents are of interest.

In 1737 Cardiff

resident John Price was brought before the courts accused of assaulting a young

girl called Anne Plumly in his garden in 1737. As well as assaulting the poor

girl, John also made a number of curious threats to Anne, principally that if

she screamed for help that ‘the spirits would come out of the friars and take

her away’. Historically there were two friaries at Cardiff, the Dominican

friars (black) and the Franciscan friars (grey). John also said that Anne would

be visited by what was described as ‘a mysterious being called the Bully Dean’,

one can only guess the nature of this supernatural entity, although the ‘bully Dean’

may have been a well-known figure in the local folklore of the area at the

time.

In 1784 Cardiff

resident Richard Griffiths, described as ‘an evil disposed person and disturber

of the peace’ attempted to provoke William Lewis of Whitchurch to fight a duel

against him by way of a written challenge. The outcome is not recorded. But in

1792 Cardiff miscreant Richard Griffiths was at it again. Richard was no common

criminal though having been described as a ‘surgeon and coroner’ but was

convicted of attacking John price, also a gentleman, by assaulting him with the

butt end of a riding whip.

Perhaps one of

the most notorious incidents of affray from this period of Cardiff’s history

was the famous riot of Homanby (now Womanby Street) in 1759. It was not really

a riot as such but more of an armed confrontation between the rival crews of two

ships. The incident saw the crews of a Bristol merchant ship called the Eagle

do battle with the crew of a man o war called the Aldbrough. HMS Aldbrough was

a 20-gun Sixth Rate ship commissioned to serve in the Caribbean, but was no

longer a serving navy ship at this point having being sold out of service in

1749 at Deptford for the sum of £302. Both crews were well armed with the

conventional weapons of the day which were commonly found of ships of all

purposes from this period such as cutlass’ (a short sword), pikes, swords,

pistols and muskets. The fight must have been ferocious as one man was killed.

The cause of this disturbance is not known although mass brawls and serious

outbreaks of organised violence were not uncommon in the Cardiff of past - times.

It was not just

sailors or civilians involved with casual violence in late Georgian Cardiff,

the military sometimes got involved. In 1801 John Quin, who was a dragoon trooper

(heavy cavalry) of the 6th Inniskilling regiment, violently robbed a

labourer called James Morgan on a bridge taking two half-crowns and 5

shillings.

Accidental

death

The records from

Cardiff at this period are replete with examples of accidental death. Death by

drowning seems to have been common. This may not come as a surprise as Cardiff

is intersected by rivers and was a port town. In 1746 Thomas Price was

accidently drowned in the river Taff by somewhere called Cardiff Key –

incidentally, Thomas was a sailor but, it was an irony that sailors of this

period were very superstitious and, being able to swim was widely regarded as

one of the many things which could bring bad luck upon a ship. In 1750 a small

boy by the name of Robert Tanner fell into the river at a place called Gollgate

and was drowned. In 1752 a coroner’s inquest found that another young boy by

the name of John Lewis was caught out by the incoming tide in an area known as

the Dumball. Despite attempting to wade through the water, the lad was suddenly

engulfed and was overcome.

(Mid eighteenth-century view of Cardiff by Paul Sandby. The river Taff was diverted west from its old course as seen in this picture to its present location in the early 1840’s by celebrated engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The river Taff originally flowed through what is now Westgate Street. Source. Source, Museum of Wales)

Water was not

the only medium which could asphyxiate an individual. Probably one of the most

unfortunate persons who died in eighteenth century Cardiff was a lady by the

name of Christian Lewis. It was the verdict of a coroner’s court that Christian

‘met her death by falling into the privy’ (a toilet) of a long vanished ancient

Cardiff pub called the King David in 1750. It was most likely that the poor

lady was intoxicated.

The town of

Cardiff was still in a rural setting at the end of the eighteenth century and

the surrounding countryside could be fatal if care was not taken. In 1772 John

Williams, on the 11th March was traversing the lonely moors which

once surrounded Cardiff and became stuck in a bog or muddy quagmire with the

unfortunate man being unable to extricate himself without assistance. John

eventually died of starvation with no one hearing his pitiful cries for help.

Even on the dawn of Cardiff’s assent to the world stage with the construction of its first dock in 1839, Cardiff was still very much a city unaffected by urban expansion. Indeed, it still very much retained its rural setting, unaffected by creeping industrialisation. This was observed by an English tourist in the 1840s:

‘The wide

plain of Cardiff affords, for many miles, gratifying prospects of various

cultivation, and several villages’ (now all absorbed into the greater area

of Cardiff, such as Whitchurch).

The rapid

industrialisation of the area however did not go unnoticed upon the visitor as he remarked:

‘Cardiff,

which stands in the flat country near the mouth of the Taff, and was, until

this few years, of no great importance, although it had a name in history. But

the rapid development of the iron trade in the Taff valley and its branches,

the canal and railroad to Merthyr, and above all the formation of a new channel

and docks, by the patriotic enterprise of the noble Marquise of Bute, have

rendered it a place of immense and increasing commercial prosperity.’

(Mid nineteenth century view of Cardiff depicting its urban expansion-a precursor to the city that we know today)

The visitor also

remarked upon the changing face of Georgian Cardiff saying:

‘This great

commercial development has of course much improved and modernised the

antiquated town of Cardiff, which is in reality the county town of Glamorgan.’

Cardiff’s future

as a leading centre of industrial prominence was sealed.

Mark and Jonathan Lambert are writers based in the Vale of Glamorgan. They are both archaeology graduates of Cardiff University and have written a number of books. They have been writing about and researching local history for the past 20 years. All articles are original compositions - we hope you enjoy our content.

Enquiries: hiddenglamorgan@outlook.com

©Jonathan and Mark Lambert 2022

The right of Jonathan and Mark Lambert to be identified as Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted, reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic means, including social media, or mechanical, or by any other means including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors.

No comments

Post a Comment