The highlight of any visit to a medieval castle

for most would likely be a visit to its dungeons. Most large castles throughout

Britain seem to contain one of these dank and uninviting underground chambers, which

in the popular imagination invokes images of incarceration, wretchedness and

despair, with the unfortunate prisoner confined in claustrophobic darkness until

they succumb to madness or starvation-sometimes both. Or so the popular belief goes,

for medieval castles and dungeons appear to be synonymous with one another.

Dungeons often feature in the castles of films

and tv programming. Monty Python and the Holy Grail for example, contains a

dungeon scene, with the prisoner despite his wretched situation, still managing

to clap along to ‘Knights of the Round Table’, and Blackadder the First,

whereby Edmund is imprisoned in a dungeon alongside ‘Mad Gerald’.

There are no doubt many other examples of this widespread

conception throughout film and television. If one, however, looks closely

beyond the popular idea of castle dungeons, there appears to be very little

evidence that these dark and concealed places were utilised for such purposes.

Or at least if they ever were, that was not their original function.

The Gothic Revival Period

The idea of a castle dungeon does not receive

much-if any attention before the Gothic revival epoch of the late Georgian

period. This was a time when an interest in the medieval past of Britain first began

to emerge. Castles and ruins became tourist attractions and interest in their

histories captured the imagination of many. Knowledge on these ancient structures and

edifices, however, was limited. In fact, romance and ruins went hand in hand.

Legends and folklore played a large roll in interpreting many aspects of the

ancient ruins that are scattered across Great Britain, especially prehistoric

monuments and of course castles, including the interpretation of underground

rooms as dungeons.

Knowledge on these buildings was not very well

developed at this time as archaeology and history as subjects and disciplines

were very much in their infancy, being the almost sole preserve of private

gentlemen who through their enthusiasm, study and scholarship laid the

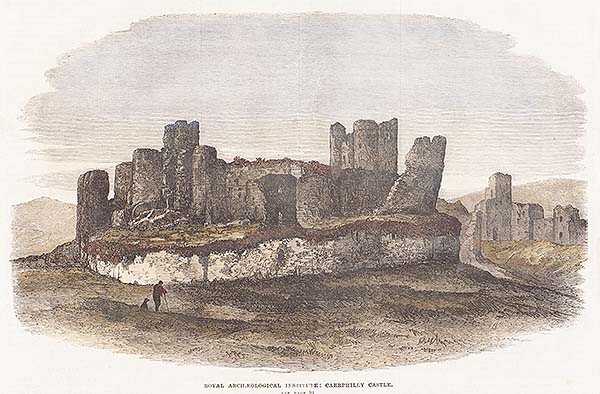

foundations for these popular subjects today. A good example of this scholarship is the work

of antiquarian G.T Clark (1809-1898), a pioneer of castle studies who, in 1834 ascertained

through a detailed survey that Caerphilly Castle was medieval in origin and that

it was initially constructed by a powerful Anglo-Norman lord called Gilbert de

Clare (1243-1295), as before this time the popular belief was that the castle was

a Roman structure.

The Gothic Novel-A Catalyst?

At around the late eighteenth century the

Gothic novel, a fiction genre characterised by stories of mystery, horror and

hauntings, which were themselves inspired by the romance and mystery of

medieval architecture, was born. Authors Horace Walpole (1717-1797), Walter

Scott (1771-1832), Mary Shelly (1797-1851), and Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849) to

name a few, helped popularise this enduring literary genre. Although not

considered a gothic author, French author and playwright Alexander Dumas’s

(1802-1870) novels in particular helped to spread the idea of the castle

dungeon. The Count of Monte Cristo’s Chateau d’if and The Man in The

Iron Mask were both works of Dumas that helped conceptualise within the

public’s imagination the idea of the castle dungeon of despair where prisoners

were locked away indefinitely, even if the time period within the novels was

much later than the medieval era.

Dungeons of Despair?

If one however looks critically at the dungeons

that many castles exhibit, there are explanations to suggest that there was a far

less sinister use for these underground places. Probably the most well-known and

commercial example of a castle dungeon is located at Warwick Castle. These claustrophobic

subterranean chambers are promoted as a place of horrific incarceration, in

particular that of French prisoners during the Hundred Years War, who were said

to have been chained in darkness. The dungeons at Warwick Castle even contains

a separate oubliette. Oubliette is a French word meaning to forget. The

interpretation many have placed upon these bottle-shaped underground rooms is the

idea that the prisoner is essentially lowered into the oubliette and is left there

to undergo psychological punishment and perhaps to eventually starve to death within

its dark and claustrophobic confines.

There however does not appear to be any

contemporary evidence to suggest that prisoners during the medieval period were

confined in oubliettes, or indeed dungeons. This grisly interpretation is

essentially a product of the Georgian and Victorian period.

The most likely explanation for these

underground rooms is that they were storage places for perishable goods such as

food and wine. A good example of this misconception can be found at Chepstow

Castle in Wales. As with most large castles in Britain, Chepstow Castle became

a tourist attraction during the nineteenth century. Tourists during the

Victorian period were seemingly able to purchase a guided tour of Chepstow

Castle. The vaulted cellar at Chepstow Castle, which is located directly

adjacent to a steep precipice flanking the river Wye, was at the time

interpreted as a dungeon. This room, however. was actually a storage depot and

wine cellar for the earl’s wine. Due to its location, wine could be winched

directly up from boats below. An iron ring which was extant at the time, was

said to have been used to chain prisoners. The ring, however, was actually used

as an anchor to help winch up provisions.

It was for the most part important and noble

prisoners who were held in castles, but more than likely in a secure room

within a tower than a dungeon to await trial, execution, ransom and sometimes,

as a place of lifelong incarceration.

History records the fate of the Duke of

Normandy Robert Curthose (1051-1134). Being the eldest son of William the

Conqueror, Robert was a powerful and important man who was involved in the

power politics of his day, including participating in the First Crusade. Robert

however was in conflict with his brother Henry and after a good deal of strife

was eventually defeated in battle and imprisoned for the remainder of his life.

History does not record the exact details of Robert’s imprisonment, but he must

have been treated well as he died during his early eighties at Cardiff Castle.

Another good example is that of political

prisoner Gruffedd ap Llewelyn (1196-1244), who was incarcerated at the Tower of

London by king Henry III. Gruffedd however had other ideas and attempted to

escape from his place of confinement, which was likely a tower, by climbing out

of the window via a number of sheets which he had tied together. The unfortunate Gruffedd, however, owing to

his weight, caused the improvised rope to break, and thus fell to his death.

Once the feudal period had ended many castles

were left to crumble and were robbed of their dressed stone. Some however, owing

to their strong structures, began a new lease of life during the post medieval

period and were converted into usage as prisons. A good example local to the

authors is St Quentin’s Castle within the Vale of Glamorgan, the gatehouse of

which was maintained as a prison long after the castle’s initial function as a bastion

of feudal power had ended. Caerphilly Castle’s gatehouse too also served as a

prison during the post medieval period as did no doubt many a castle gatehouse.

It is perhaps from this period that the medieval castle began to gain its

reputation for containing dungeons of incarceration, which in turn inspired the

romanticising of the dungeon in Georgian and Victorian imagination.

It is from this period however that there is

evidence to suggest that a number of unfortunate individuals were imprisoned in

what could be described as dungeons of despair.

Dungeons of Despair

Prisons, until fairly recently, have always had

a reputation for hardship and often, brutal and inhumane conditions. One

unfortunate prisoner who had it worst than most was James Hepburn, fourth earl

of Bothwell. James, who was on the run from his enemies in Britain fled via

boat and found himself adrift near Norway. James was taken prisoner and sued

for abandonment by his estranged wife Anna Throndsen. After a short while James

was handed over to Danish king Frederick II. At the end of much deliberation

Frederick decided to lock Hepburn up-and throw away the key (so to speak). The

unfortunate Hepburn was thus for the rest of his life chained to a wall of various

castles throughout Sweden and Denmark. James died in a dungeon in Dragsholm

Castle in 1578 in what were said to have been appalling conditions with some chroniclers

recording that the earl went mad.

(The unfortunate James Hepburn, who was reputed to have spent the last six years of his life chained to the wall of a dungeon)

St Briavels Castle in the Forest of Dean, like

many castles around Britain was converted into a gaol after the medieval

period. St Briavels was notorious for its appalling and inhumane conditions as

a debtor’s prison. An interesting piece of graffiti is to be found etched upon

the walls of St Briavels which reads ‘the day will come that thou shalt

answer for it for thou hast sworn against me, 1671’, St Briavels is a YHA

youth hostel and if one so wishes, can stay the night. Owing to the castle’s

haunted reputation it is a popular place with those who crave a supernatural experience

as well as with history enthusiasts.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that the castle dungeon was

essentially a product of the late Georgian period, there is some truth to the

belief that many of their subterranean rooms served as places of confinement

and incarceration-just not during the medieval period or perhaps in such a

grisly way as many believe, and almost certainly not as depicted at Warwick

Castle. It was during the post medieval period where there is evidence that

many of Britain’s medieval castles, which by this time were obsolete, began

their new lives as precursors to the modern prison.

It is most likely that, given their

dishevelled, damp and uninviting atmosphere, castles, in particular the

subterranean areas became associated with suffering and misery and that,

despite no real evidence for their use as places of incarceration during the

medieval period became synonymous with the cruel treatment of prisoners.

Mark and Jonathan Lambert are writers based in the Vale of Glamorgan. They are both archaeology graduates of Cardiff University and have written a number of books. They have been writing about and researching local history for the past 20 years. All articles are original compositions - we hope you enjoy our content.

Enquiries: hiddenglamorgan@outlook.com

©Jonathan and Mark Lambert 2023

The right of Jonathan and Mark Lambert to be identified as Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted, reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic means, including social media, or mechanical, or by any other means including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors.

No comments

Post a Comment